The time capsule of an old tribute

By Jamie Passaro • February 13, 2018

The first person I knew well who died was also the first person I “went out with,” though in actuality we went very few places aside from walking home from school together. We held hands until there was a car coming, and then I’d let go, afraid someone would tell my parents in our tiny town. He had braces and a bowl cut of thick sandy hair, an impish smile that made his eyes crinkle, and a loud laugh that I can still hear. He used to stand behind me at my locker in the morning with his arms around my waist. Steven James. My friends called me James, and so we thought it was clever to call ourselves Steve-n-James. Steve wrote it in pencil on the desks at school. He also wrote my bra size, for some reason only a seventh grade boy would understand. My parents liked him and invited him over for family movie nights on Fridays and once we all watched Bull Durham in our living room, my Mom picking it out because Steve liked baseball so much. During a scene with a sex toy, I thought poor Steve was going to explode with stifled laughter—I had no idea what it was. My mom and dad gave us our own space to watch movies after that, and my dad would wander by every half an hour or so and we would straighten ourselves and pretend we were watching whatever PG movie Mom had rented for us.

The first person I knew well who died was also the first person I “went out with,” though in actuality we went very few places aside from walking home from school together. We held hands until there was a car coming, and then I’d let go, afraid someone would tell my parents in our tiny town. He had braces and a bowl cut of thick sandy hair, an impish smile that made his eyes crinkle, and a loud laugh that I can still hear. He used to stand behind me at my locker in the morning with his arms around my waist. Steven James. My friends called me James, and so we thought it was clever to call ourselves Steve-n-James. Steve wrote it in pencil on the desks at school. He also wrote my bra size, for some reason only a seventh grade boy would understand. My parents liked him and invited him over for family movie nights on Fridays and once we all watched Bull Durham in our living room, my Mom picking it out because Steve liked baseball so much. During a scene with a sex toy, I thought poor Steve was going to explode with stifled laughter—I had no idea what it was. My mom and dad gave us our own space to watch movies after that, and my dad would wander by every half an hour or so and we would straighten ourselves and pretend we were watching whatever PG movie Mom had rented for us.

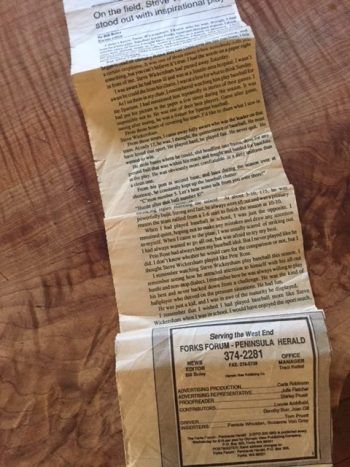

Steve gave me a teddy bear for my birthday that first year when we were going out and I still have the skin of it, the stuffing having been removed in a fit when I heard a rumor that when we were broken up he’d messed around with another girl in the woods behind his house. The bear is kept in a dusty blue box along with a postcard he sent when he went to Maui once, the handwritten words to Bon Jovi’s “I’ll Be There For You,” a dried-up homecoming corsage, and a column the local weekly newspaper editor, Bill Buley, wrote when Steve died the summer before our senior year, all about how Buley wished he’d been more like Steve as a baseball player.

“At only 17, he was, I thought, the quintessence of baseball,” Buley wrote. “He must have loved that sport. He played hard, he played fair. He never quit. He wanted to win . . . He stole bases where he could, slid headfirst into bases, dove for any ground ball that was within his reach and fought and battled for base hits at the play. He was obviously more comfortable in a dirty uniform than a clean one.”

The column goes on to describe Steve as a “menacing figure” (he had shaved his hair and grown a goatee by this point) on the infield with “all-out hustle and non-stop dialect.” He compares Steve to Pete Rose, his idol. “He was just a kid,” he writes, “and I was in awe of the maturity he displayed.”

It’s a beautiful tribute—without being overly sentimental, which is a hard thing to do when you’re writing about the death of a 17-year-old.

Reading that column was the first time I realized that words could help memorialize someone. Or maybe I didn’t fully understand that then, but I understand it now, twenty-five years later, the power of typed words on a yellowed newspaper scrap. Sure, I have my memories, too, but what Buley captured is now this object that helps me remember.